A Little-Known, Crazy Story of FBI Infiltration on a Movie Set

In October of 1968, American movie studio Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) signed a one-movie contract with Italian filmmaker and director Michaelangelo Antonioni (1912-2007). MGM had previously experienced financial success when they distributed Antonioni’s first English-speaking film, Blowup, in the United States. They were salivating to make bank off what was sure to be another hit from the acclaimed director. Instead, mere weeks into filming, they found themselves saddled with repeated production delays, an increasingly bloated budget, and a script they loathed and politically feared. During filming, Antonioni claimed he thought the FBI had tapped his phones and that some of the extras on set were undercover agents. He was right. The FBI had infiltrated his movie, mostly thanks to one actress in the film’s opening scene who was also rumored to be his unofficial advisor on set: Kathleen Cleaver, whose husband was then on the FBI’s Top Ten Most Wanted List.

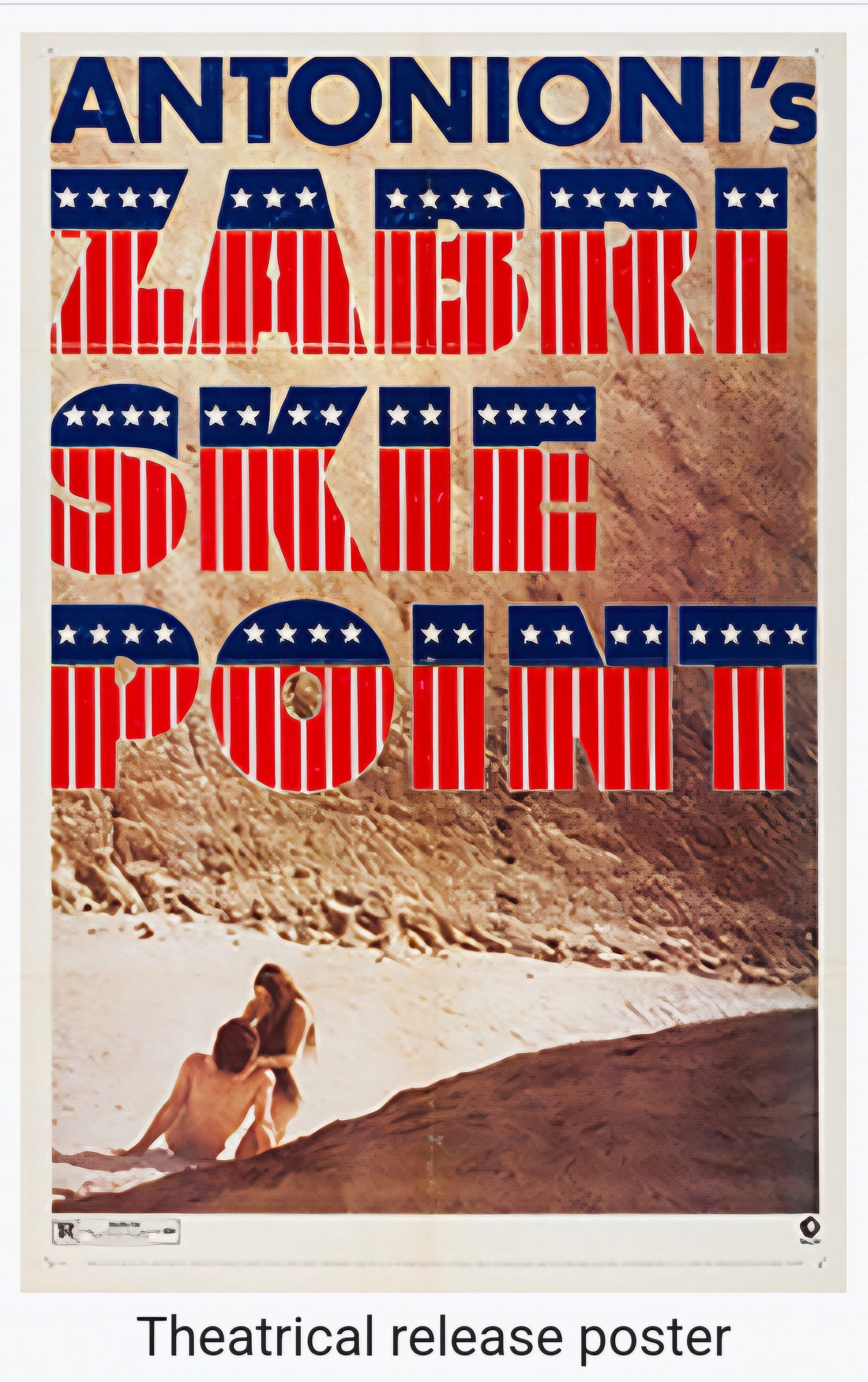

This is the rather insane story of Zabriskie Point.

After a string of successful Italian films, Antonioni partnered with a production company to cross over into English-speaking films. His first of three was Blowup, an erotic thriller set in swinging London, starring Vanessa Redgrave and David Hemmings. MGM optioned Blowup for a US nationwide release, to great critical and commercial success.

MGM signed Antonioni to make a second English-speaking movie. The contract gave the director near total creative autonomy, a decision the studio would later deeply regret. They were expecting another erotic thriller in the style of Blowup, this time more specifically for American audiences. But Antonioni went in a different direction.

Since residing in America, he had become fascinated with student activism and anti-war protests, and he wanted to write a script centered around campus radicals. He began his research by conducting a series of interviews of student radicals on West Coast college campuses. This was leaked to the trade magazines, which were no doubt read by the studio heads. MGM was not impressed.

Antonioni wrote his script, with one scene calling for a “love-in”, where hundreds of couples would make love outside in the Death Valley sand dunes. The scene called for explicit nudity and simulated sex, still a controversial phenomenon in American cinema at that time.

The National Park Service disapproved and denied permission to shoot any scene in Death Valley. Environmental activists responded with a mass letter-writing campaign to the Park Service in Washington, D.C., asking them to repeal the decision, which they did. In response to the D.C. Park Service’s decision, a group of conservative park rangers sent letters of complaint to MGM and all law enforcement agencies in Washington. This is probably how Antonioni’s movie initially caught the attention of the FBI.

The filmmaking process inched forward. Antonioni upset MGM again with his casting choices. He eschewed bankable stars in favor of unknown actors; but the word “actor” here is a bit too generous. Antonioni plucked his male and female leads out of complete obscurity, with neither having ANY acting experience under their belt. Daria Halprin was chosen as the female lead; the daughter of a Haight-Ashbury-based dancer and a dancer herself, she was chosen from her brief appearance in a documentary about San Francisco’s hippie movement. Mark Frechette, the male lead, had zero acting abilities, but did have a history of violence and mental illness, and was at the time a member of singer Mel Lyman’s Boston-based anarchist cult. MGM was less than thrilled. But, thanks to the artistic freedom they contractually gave over to Antonioni, there was little they could do.

Principal photography began. MGM hired the crew, who were mostly political conservatives, likely Nixon supporters. They loathed and feared the European director, calling his previous film Blowup a “dirty movie” and the man himself “a pinko dag pornographer”. The crew was uncooperative and subversive: they reported every single tiny union and industry rule violation to cause production delays and bloat the budget. They made a series of anonymous calls to their union representatives, reporting the film and director as “un-American” - this resulted in multiple instances of the unions calling for shutdowns and sick-outs.

Principal photography wrapped in April of 1969. Less than one month later, several major players in Antonioni’s production company were named in a criminal action. The U.S. Attorney’s office alleged a Mann Act violation. The Mann Act prohibited transporting humans across state lines for “immoral purposes.” Many of the extras for the Death Valley love-in scene were hired and bused across the country from a theater company in New York. The press and trade magazines denounced the criminal action as petty, overtly political, and without merit. Beginning in May 1969, eleven people were summoned to a federal grand jury in Sacramento (some crew members came forward as voluntary witnesses eager to testify against Antonioni), and “certain records from the production” were subpoenaed.

The movie hit theaters in February 1970, at which time the Justice Department said they were still investigating the case. The outcome of this criminal action is uncertain. In 2015, a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request was made to the Department of Justice, who said to contact the FBI, who said to contact the National Archive and Records Administration, who claimed they never received copies or records of the case.

Eldridge Cleaver

It’s unclear how Kathleen Cleaver met Michaelangelo Antonioni, or even the extent of the role she played in shepherding Zabriskie Point to its eventual theatrical release. But her husband’s entanglements with law enforcement, including the feds, are undisputed.

Eldridge Cleaver was born in 1935 in Wabbaseka, Arkansas. By his teenage years, his family had settled in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, California. He began dabbling in marijuana as a teenager, and eventually found himself serving two years in Soledad state prison for possession. He obtained his high school diploma while incarcerated. About one year after his release, he was convicted of rape and assault with intent to murder and sent first to San Quentin, then Folsom prison. In jail, he became a Black Muslim convert, then a devout follower of Malcolm X. He began writing essays in jail, and through his defense attorney, got them published in San Francisco-based Ramparts magazine. In December of 1966 he was granted parole and a job at Ramparts. There he met Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale, co-founders of the Black Panthers. Cleaver joined the organization and became their minister of information. In 1968, the essays he penned from prison were published as his memoir, Soul on Ice.

In April of 1968, after Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated, Cleaver was involved in a shootout in Oakland between the Panthers and the police. A young Panther member named Bobby Hutton was killed. Two cops were wounded, as was Cleaver. Cleaver was arrested for his role, then he jumped bail and fled to exile in Cuba. About a year later, he moved to Algeria where he attempted to found an international wing of the Black Panthers.

By 1971, Cleaver and Newton had fallen out, and Cleaver had become disillusioned with political radicalism, so he officially left the Panthers. In 1977 he returned to the United States and turned himself in to the FBI. He negotiated a plea deal that resulted in a punishment of 1200 hours of community service. Between 1971 and his death in 1998, he bounced around in life, ideologically speaking. After becoming critical of the Black Panthers he turned to evangelical Christianity, but didn’t stay there. He also tried on Catholicism, attempted an entrepreneurial life, and suffered from addiction. By the early 1980s he identified as a political conservative, and ran for office a few times, unsuccessfully, as a GOP candidate. His wife divorced him in 1987, and he died quietly in 1998.

Zabriskie Point’s bloated budget swelled to $7 million total, a staggering amount for the late 1960s. Its theater release was a complete flop. The movie grossed $1 million total, and critics universally panned it. After the movie wrapped, the two leads, Halprin and Frechette, became a real-life romantic couple, and Frechette returned to his cult/commune with Halprin in tow. A few years later, Frechette participated in a Boston bank robbery on behalf of the cult leader, landed himself in prison, and died there in a freak weight-lifting accident.

More recently, a remastered digital version of Zabriskie Point was released, and its new audience is somewhat more appreciative, finding that even with its flaws - most notably the terrible, flat acting - Antonioni did accurately capture the zeitgeist of the time.

SOURCES:

Hollywood v. Hard Core: How the Struggle Over Censorship Created the Modern Film Industry by Jon Lewis

“Sex on the Desert: Was Zabriskie Point—Antonioni’s biggest flop—just misunderstood?” by Dennis Lim, Slate, July 14, 2009

“Sacramento federal grand jury investigation into alleged Mann Act violation (1969-1970)”, History Hub, historyhub.history.gov

“Michaelangelo Antonioni, Obituary” by Penelope Houston, The Guardian, July 31, 2007

“Eldridge Cleaver, Black Panther Who Became G.O.P. Conservative, Is Dead at 62” by John Kifner, New York Times, May 2, 1998

“Ex-Panther Says He Saw Cleaver Kill a Man” by David Rosenzweig, Los Angeles Times, February 24, 2001